For the next 4 weeks we will be diving into the ‘The Tailor of Hereford’ book written by the incredible historian John Harrison. Week by week we will be uploading a chapter of the book. We will introduce you to the ever growing history of Pritchards dating back to 1836.

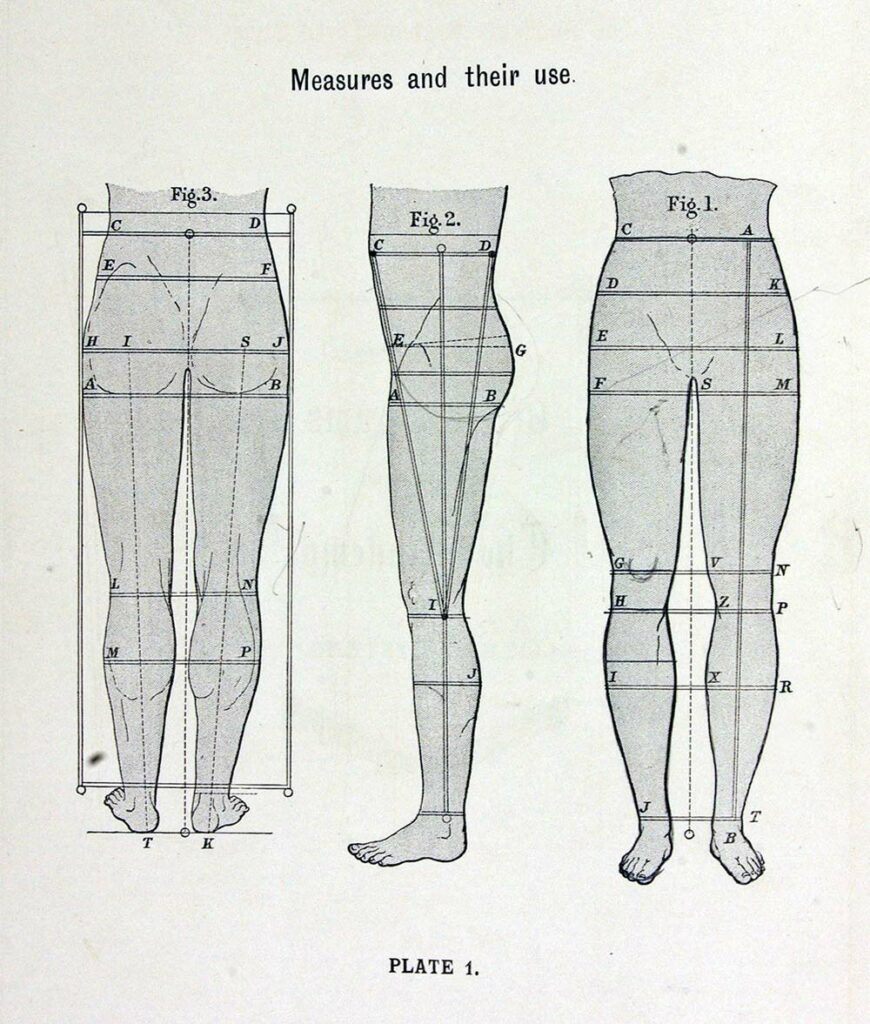

Every tailoring firm has two tasks to perform. The first task is that of measuring the customer, then of drawing on his chosen cloth the shapes which will turn into the arms, the back and front of a coat, with its collar and lapels, its pockets, inside and out, with or without flaps, and so finally of cutting out of all these pieces, with due allowance for seams, tucks and pleats. That is the role of the cutter, here taken by the successive generations of Prichards from William in 1836 to Edward in the 1950s. The second task is that of the sewing-tailors and sempstresses who assemble those pieces into garments Behind the Pritchard men there can always be heard the tramp of a back-stage army, that of their sewing tailors, ten, a dozen, perhaps more. Who they were, where they came from, how they had been recruited, what they were paid is nowhere formally or regularly set down.

Probably the nearest we can get to understanding how they got to Hereford is by reading the reminiscences of men like George Robertson.’ As a journeyman- tailor he had set off on foot from Alnwick in Northumberland for London, earning his keep on the way. Once arrived, he had joined a House of Call’, the King’s Head in Bear Street, Leicester Square. ‘My name was entered on the roll, and I agreed to make at least three calls a day to see if I was wanted. The time of the first call – 9 a.m. was compulsory … as was the second call at 1 p.m. Of course, all this hanging about led to a good deal of drinking. The King’s Head took its profit and he did find a job – in Saville Row. Robertson’s story leads to the question whether the recruitment of tailors followed a similar pattern in Herefordshire, with the Number Five pub in Widemarsh Street playing the role of a House of Call for Hereford?

The first of Prichards’ staff to be named is the Kington lad, William Tringham, the handyman-/journeyman-tailor who lived with William’s family in the earliest Bye Street days. From 1860 to 1871 A. McMullen became a trusted member of the team, though nothing otherwise is known about him before his short spell in charge at 41 Broad Street. A gap follows before the census of 1891 records two very Herefordian names, those of Francis E. Pudge, then 16, a tailor’s assistant and Percival W. Meats at 15 a tailor’s appren- tice, both shown to be housed in the shop itself. (In 1909, when he witnesses Susan’s will, Meats is identified as ‘Assistant, 1&2 Commercial Street.) All the rest are anonymous, bar one – the Thomas who is pencilled into the margin on the penultimate page of the first tailoring ledger above a list of numbers: 10¼, 10¼, 10¾, 4½, 10¼, 11¼ and then 57¼ – the hours worked in his six-day week with its half day on the Thursday but a late evening on Saturdays.

The move to early closing on Saturdays as well as Thursdays was first accepted by the banks and great department-stores, vigorously pushed by such trade unions as the Amalgamated Society of Tailors and Tailoresses, who went on strike in 1909 for improved conditions. Their demands were twice rejected by the great London stores, Peter Robinson, Debenham & Freebody, Jay’s, Marshall & Snellgrove, and others. But, we are told, Whitsuntide was approaching, lady customers were everywhere crying aloud for the execution of their orders’, so after much haggling agreement was reached. The Amalgamated Society accepted a 50-hour week; Christmas Day, Boxing Day and Easter became paid holidays; overtime would be paid on Saturdays after 2pm.? Here are foreshadowed the Saturday afternoons off together with the national holidays we once took for granted, though these now are so often devoted to mammoth sales or car boots. To this reminder that before the First World War, while factory legislation had limited the working hours of children, there was no protection for adults outside the factory, nor laws about health and safety in shops, Percy, interviewed by Bill Laws, adds his vivid comment:

“In those days everything was made by hand and as many as 12 tailors occupied the workshop and of course wages were very low. … young people were put to the tailoring and the boot trade that were not able to do other things … like cripples. When I was put to learn the sewing under a tailor in this workshop at the end of the week I used to make up what they called their log, their wages in a little book, [a] tailor making a jacket or a waistcoat or trousers, working from fairly early in the morning – eight o’clock probably – up to seven in the evening, 18s 6d. If he was on dress wear. 25s. Dress clothes were finer work. And there were no holidays with pay, there was no hospital or anything like that. I know my grandfather used to subscribe to the hospital, what they used to call papers. They used to come to him and say can I have a paper to go to hospital’.” When they were out of work of course there was only the workhouse. And yet they brought up families on that and there were some very cultured tailors in those days.”

Percy goes on,

“My grandfather also introduced the half-day closing, Thursday half-day closing.* That was the first progress there was in sort of relieving the tension in the labour market. [They were paid for the half-day holiday| but the wages were very low. And really when you come to think of it, even between the two wars … the average wage for a South Wales coal miner was only 50s.”

That comment, sympathetic in tone, is all that we have on Pritchard wages before the First World War. Many of the tailors employed, Percy says, were travelling tailors like Poles and Germans and Irishmen, working for a while and then going off somewhere else. During their long spells working cross-legged in a circle most would keep a quid of chewing tobacco in their mouths to keep them going and had some secret formula for getting nicotine stains out of the clothes they were stitching. Others, however, broke the tensions of the long day and week by taking a day off to drink their devotions to Saint Monday. She was a favourite in the years before unrelenting factory machinery imposed regularity – as Percy recalls:

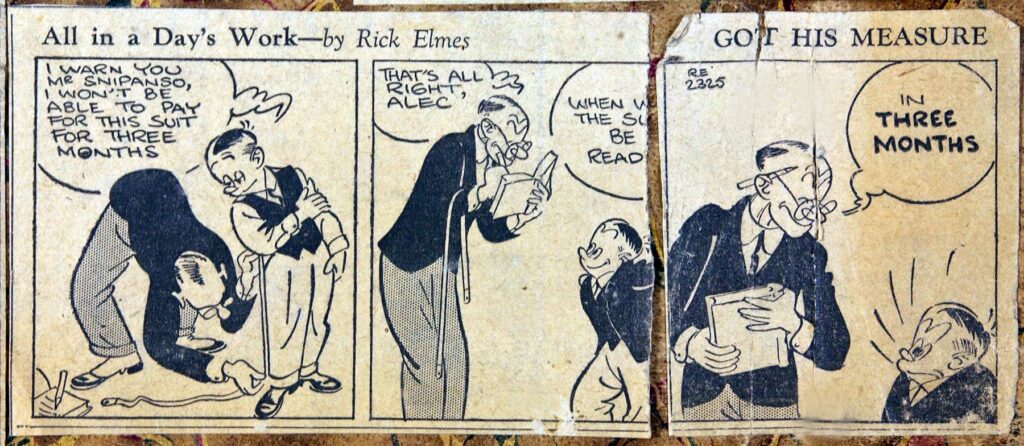

“Some were heavy drinkers. They’d go out and they’d drink for a week. There was a pub in Widemarsh Street that the tailors haunted, it was called Number Five.” Some would go there and they’d drink, drink, drink. Then they’d come at the end of the week and they’d ask my grandfather for the boot’, that was just a half a crown to get another drink. Then they’d work away again like this. But of course their conditions made them go off the handle like that.”

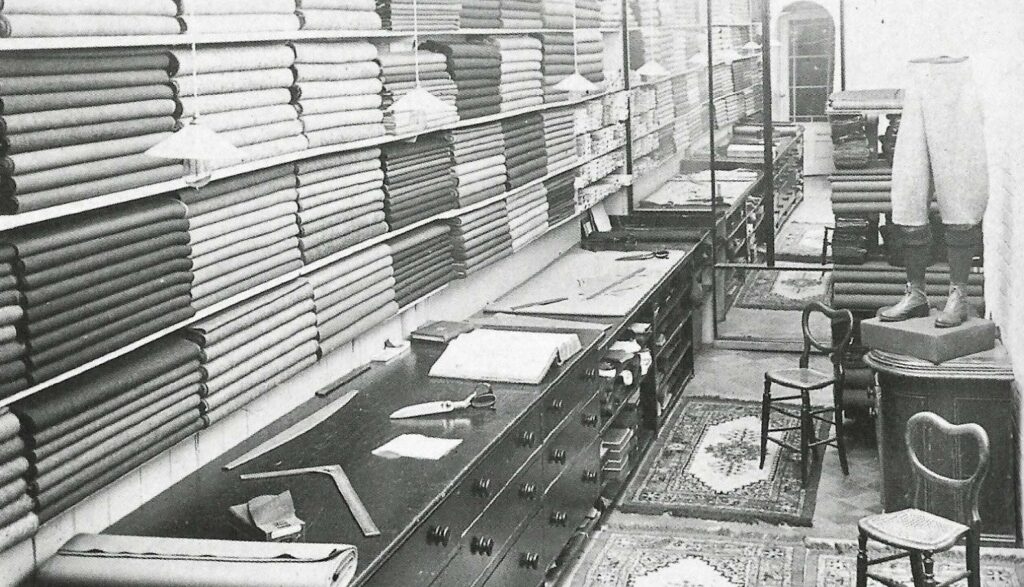

Percy might have instanced the cramped 240 sq. ft workroom, presumably ill-ventilated, which their cross-legged circle of tailors worked in, lit by a window and doorway opening on the shop interior. Fortunately drink was the one item of personal spending which fell – and fell sharply – between 1910 and 1938. We do not even know how the front of the shop was manned, though the fact that Pritchards were outfitters as well as tailors meant that a wide variety of customers would have been received from behind those mahogany counters, with each customer seated while a male counter-hand displays a selection of collars and shirts or unfurls a roll of cloth for him . It would be later that the bespoke client was taken to the measuring and fitting room upstairs.

A further question is raised by the presence on page 849 of the first tailoring ledger of a list of names and addresses. They are those of past or potential tailors, mainly local. They include one woman seeking a place – her daughter is employed by Morgan, a rival tailor. The rest are men identified by their specialist skills and training. So, a Polish man, Mathew Cucclawich, currently at 8 St Owen Street but earlier in Cardiff, is put down as an excellent trouser and breeches maker. Mr Owens of Sefton Villas is a first class coat hand, while a Mr Davies is a very good vest (waistcoat) maker. In sharp contrast, however Mr Williams is candidly described as a second-class workman, indolent, uncertain and given to drink, while another man wants one under ear’, and a third is frankly ‘no dam [sic] good’.

Several had been employed by Prichards but had left in debt or with work unfinished, Evidently this was particularly vexing in the case of one first-class dress and frock coat maker who had gone off owing 15s and leaving an overcoat to be finished by Ashburn, a more consistent hand. In the same way, Braun, a German coat maker, had left with a jacket unfinished and Prichards had to pay 7s 6d to get the job completed.

The fact that Pritchards paid to have a garment finished raises the whole question of how their workmen should be viewed. Were they a permanent body required to handle any type of order that came in? Or were they a group of specialised individuals employed on piece-work, at a set price, the 18s 6d and 25s which Percy describes as the going rate for a jacket or a dress coat, part at least paid in advance? What the evidence suggests is the latter and that Prichards’ workmen did not deal with whole suits, but exclusively with coats, trousers or waistcoats.

Piece-working would fit Percy’s picture of travelling tailors moving about the country. It would also explain why, at the very end of the ledger, below the list of possible workmen, there is a long, carefully written set of instructions under the date 9 December 1912 on the procedures to be followed by tailors when basting (tacking) and then making up a garment.

The Forward Baist. Coat The proper under collar basted on & padded, 7 rows to leaf 8 5 to stand, all stretching and shrinking in. All seams basted. All wadding baisted in & all linings in. Inclusive sleeve linings. Facings basted in. Hair cloth in, bound all round arm hole as well & the cuts to be canvas, ved. [‘V’ shaped] The fronts to be bridled with tape. The amount to be worked up ¾ inch. All out pockets in, stayed and tacked.

Similar instructions are given for basting the vest or waistcoat. They are followed by no less elaborate instructions for making up the now tacked coat and waistcoat:

The Finished Coat. To be made as follows:- The collar hand padded fall & stand & other than the stitching of edge to be made and put in gorge entirely by hand, 1 inch stand always unless otherwise stated on ticket [of instructions from the cutter] … No twisted rolls in sleeve heads … sleeves put in scye [the armhole] by hand & the seams opened in all cases … Back vent to have a linen stay & corners taped to curl toward body. Button-hole twist … not to be waxed and no gimp to be used.

Two final exhortations round off the lengthy document: “Soft finished trade & good form the essential. (Punctuality must be the rule in finishing garments.)’

The document, despite the abrupt nature of the way in which the instructions are worded, covers much of two large pages and seems to be the work of William himself, whether taken from some manual or the fruit of experience. The bombshell is to note that it is addressed, not to some regular body of tailors working away at 1 & 2 Commercial Street, but to outworkers. ‘These instructions … to be carried out as follows by all outworkers & thus ensuring a uniform standard of workmanship.’If all Prichards’ workforce were engaged on a piece-work basis, whether they were working in-house at the shop or from their own homes, these rules would clearly cover the need for uniformity.

Does this mean that William was looking to cheap casual labour to make good the contraction everyone was feeling in the bespoke trade? Or is it that piecework was quite commonplace? After all, the 19th century saw dockhands hired daily at port gates, while bus crews, like cabbies, were only paid from whatever fares they took.

It is Thornton’s Review of April 1910 which puts Prichards’ practice very much in focus. This quotes a speaker from Manchester, Mr Gordon, who is quite explicit. For newer and modern firms, he declares, out-working is the order of the day: Ignore those notices “all work done on the premises” unless you understand that the premises are those of the out- worker. It is a system made more successful because modern transport has so cut time and distance between the West End shop and out-workers’ cheap lodgings’.

‘Piece-work’ is the general thing and, except in slack times, an expert sewing tailor can make a decent living. All firms of any standing keep some men – the most reliable – regu- larly employed, who, though not theoretically on the staff are so in fact. However Gordon goes on to say that every year numbers of foreigners come to London, work the season through and go home. The best secure good wages, though for many employment is fitful and but poorly paid’. Gordon estimated that across England journeyman-tailors earned in some cases as much as 50s a week the year round, others 30s, others scarcely 20 shillings.

Amongst those who do well, according to Gordon, were the men working on the prem- ises who undertook basting, repairs and alterations. Some might sneer at them and say ‘infra dig’ but he said it should be recognised that alterations are really a quite difficult art. Finally Gordon has a word about female labour and their large role in out-work – a big majority indeed among waistcoat, skirt and trouser hands and as fellers and buttonholers. Their piece-work rates for making a waistcoat he puts at anything from 2s to 8s.

The Thornton Review in February 1910 had also set out national Board of Trade figures for September 1908 based upon the earnings of 42,810 persons in the tailoring trade. For men on the bespoke side who worked full time, average weekly pay in the North and West Midlands was 34s 1d, it was 14s 3d for women and for girls 5s, 6s, or 7s 1d. On the ready- made, factory side women formed three fifths of the total number employed and more than half were power machinists, averaging on piece work 13s 5d a week full time. Hand sewers averaged just 11s 4d. In all cases the important words are full-time’, for slack periods and short time working were common in the tailoring industry and not provided for.

Back in Hereford the memories of a local family, that of Mrs Anne Lane, partly make good what the Prichard documents fail to offer – an actual example of the firm’s relation- ship with one of its workmen, for Mrs Lane’s grandfather, William Watkin Wynne and his second wife, Emily Annie, née Lewis, both worked for Prichards. We can see the relation- ship changing over time.

William Wynne, born in 1872, was the son of an engine driver at Barton Station. By 1891, aged 19, he was a tailor’s apprentice, a boarder housed by Elizabeth Jay in Park Street. When his apprenticeship had begun and with whom he had learned his trade is not known. By 1895 however, his apprenticeship had been served and he was a journeyman- tailor, as his marriage certificate to Emily in 1899 confirms. It was as a journeyman-tailor at Prichards that the family recollect him. The 1901 census confirms that at 28 William was a worker’, i.e. employed by a firm on their premises, in this case Pritchards.

Ten years later the 1911 census shows him as a tailor – the word journeyman is crossed out – but also as a worker at home. This strongly suggests that he was an out-worker, probably working on orders from Pritchards, but may be for other Hereford firms too, able to pick and choose. It is only in the ‘Commercial’ columns of the Kelly directories of 1934 and 1937 that the name of Wynn, W.WM., Tailor, 73 Bath Street, Hereford’, finally appears, a sign of his success and his independence.